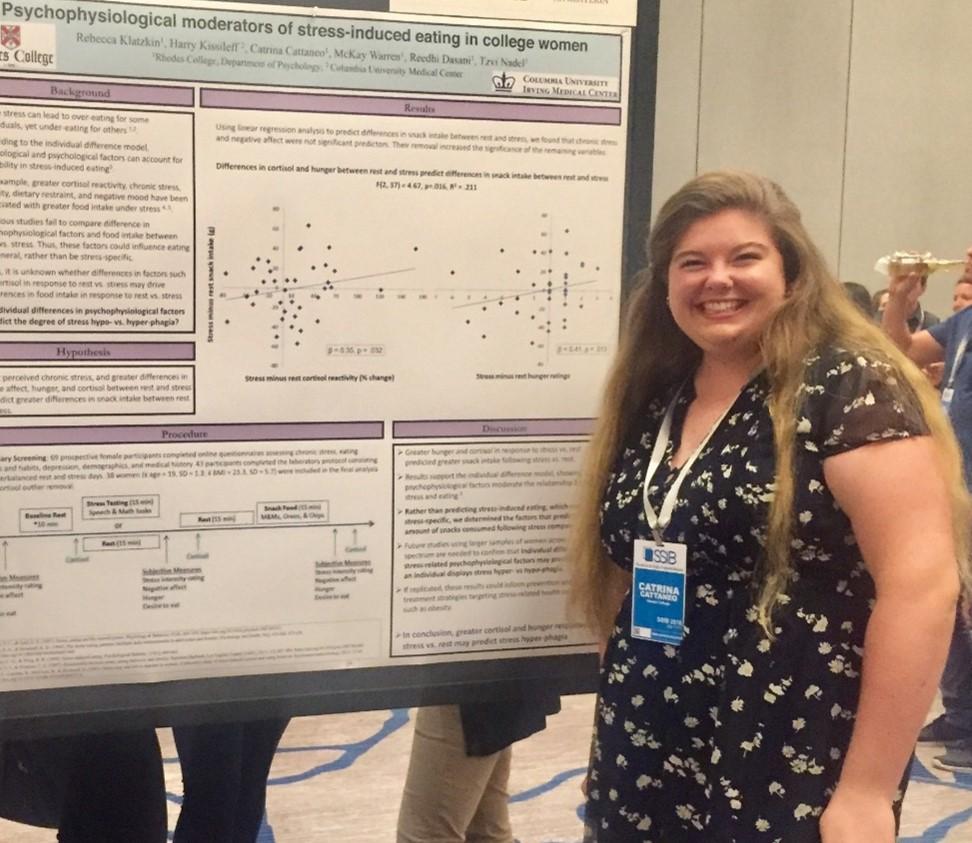

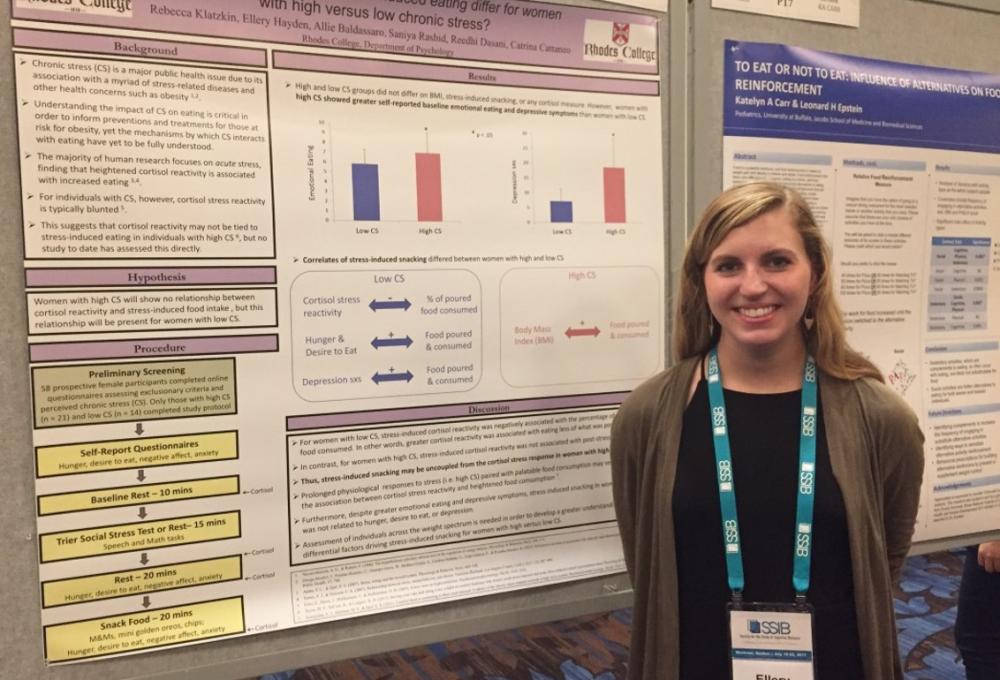

The Behavioral Neuroscience research program at Rhodes College investigates the psychophysiological mechanisms underlying stress-eating. Life stressors often prompt changes in eating behaviors toward comfort foods (i.e. palatable foods high in fat, sugar, carbohydrates, or sodium), yet the amount of food consumed under stress is highly variable. Understanding the causes of this variability in the stress-eating relationship is increasingly important given the high rates of stress and obesity in the United States, and the association between stress and a wide variety of obesity-related health issues. We examine how individual difference factors (e.g., chronic stress, perceptions about stress, mood, stress hormones) impact the stress-eating relationship and explain variability in stress-eating. Our translational goal is to help inform theory and research on stress, eating, and health, as well as targeted eating- and obesity-related treatments for women.

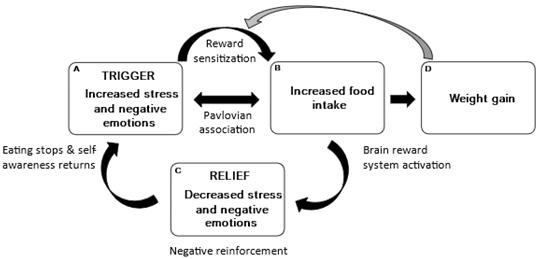

Our research is theoretically grounded and centered on investigating the emotion regulation model of eating (Figure 1). This theory-driven emotional eating cycle states that emotional eating is part of a feed-forward cycle in which greater stress and negative emotions (i.e., trigger; box A) sensitize the brain reward system and lead to more food intake (box B) and weight gain (box D). Greater food intake (box B) causes further activation of the brain reward system and leads to less stress and negative emotions (i.e., relief; box C). However, this short-term emotional relief (i.e., negative reinforcement) is not sustained, as stress and negative emotions (box A) return upon the cessation of eating. Over time, greater exposure to stressors and negative emotions (box A) is more likely to trigger food intake because of positive feedback from factors such as conditioning, brain reward processes, enhanced emotion regulation motives, and weight gain.

Our research focuses on understanding how the individual differences model of stress and eating can be applied to this stress-eating cycle (Figure 1) to explain variability in the stress-eating relationship. The individual differences model of stress and eating suggests that differences in cognition, reward learning, and physiology produce variations in vulnerability to the effects of stress. The current focus of our lab is to investigate how individual differences in stress mindset (general perception about the nature of stress) impact stress-eating.

Stress mindset can be conceptualized as the extent to which one believes that stress has enhancing consequences such as improving performance, productivity, health, wellbeing, learning, and growth (referred to as a “stress-is-enhancing mindset”) or has debilitating consequences (referred to as a “stress-is-debilitating mindset”). Stress mindset impacts our physiological and psychological stress responses in unique ways. Given that our stress responses impact our eating behaviors, our lab is interested in how stress mindset impacts the stress response to have downstream effects on stress-eating.

Learn more about Dr. Klatzkin (CV)