Opinion Essays by Professor Jackson

"How a Queer Couple Masterminded a Nazi Resistance Campaign"

"Including women's wartime stories changes how we understand warfare"

"Other cities ignore Paris floods at their peril"

"Natural disasters may cripple cities but they galvanize communities"

"Today's social unrest rooted in two histories of America"

"Lessons Paris Learned from the Flood of 1910"

Teaching

I teach a wide range of courses in European history and the history of Western culture, including ones that encourage students to look for the connections between different countries and societies. I believe that no part of the human experience is off-limits for the historian’s study. Therefore, I try to bring an array of stories, documents, and resources to my classroom in order to give students a deep sense of what it was like for people to live at a particular moment in time, including music, literature, film, art, and other kinds of sources. As a result, I try to get my students outside their own heads and into the minds of other people who lived in the past.

My courses often include surveys of nineteenth and twentieth century Europe, the comparative history of Fascism and Nazism, Europe since 1945, historical methodology, and history of natural disasters. I have also taught about the history of Paris and of France.

Research

As a cultural historian, I try to understand the ways in which people in the past made meaning out of the events, values, symbols, and practices that they experienced on a daily basis.

To learn more about my research, visit www.jeffreyhjackson.com.

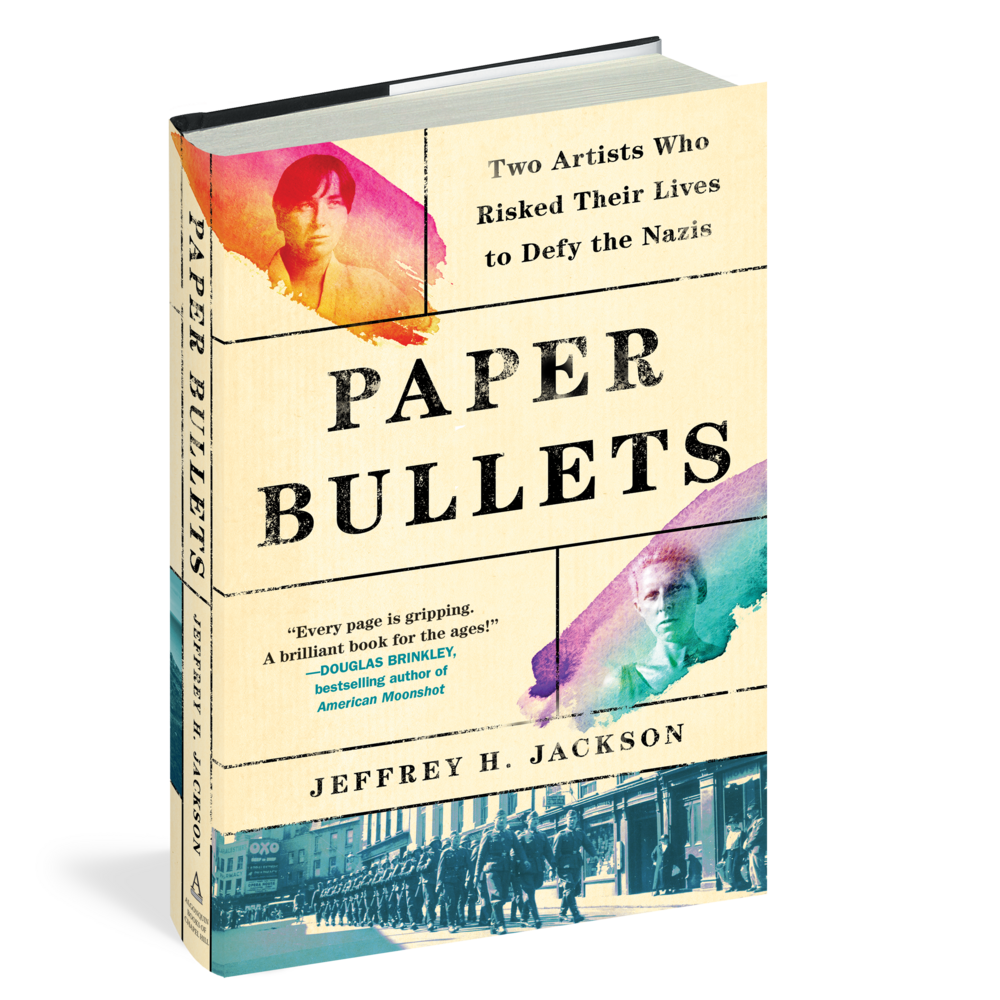

My most recent book is titled Paper Bullets: Two Artists Who Risked Their Lives to Defy the Nazis about the anti-Nazi resistance activities of the French avant-garde artists Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe. Step-sisters and lesbian partners, each took intentionally gender-neutral names for the purpose of their art; Schwob became Claude Cahun and Malherbe changed to Marcel Moore. In order to resist the Nazi troops who had occupied their adopted home of Jersey, they again created new identities to spread subversive messages to German soldiers in hopes of demoralizing and confusing the invading army. This resistance activity grew organically out of life-long patterns of fighting against the social norms of their day.

My previous monograph, titled Paris Under Water: How the City of Light Survived the Great Flood of 1910 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), tells the largely forgotten story of one of the city’s greatest disasters. At the turn of the twentieth century, Parisians believed they lived in the greatest city in the world. But Paris came to a halt in January 1910 when the river that provided much of the city’s life quickly became an instrument of destruction. Following weeks of torrential rainfall, the Seine overflowed its banks flooding thousands of homes and sending hundreds of thousands of people fleeing for safety and higher ground. This most modern of cities seemed to have lost its battle with the elements. But in the midst of the disaster, despite decades of political division, scandal, and deep tensions between social classes, Parisians rallied to help one another and rebuild. Leaders and people answered the call to action in the city’s hour of need. This newfound ability to work together proved crucial just four years later when France was plunged into the depths of World War I. What emerged from the waters, and from the war, was the Paris we know today. The story of Paris coming from the flood waters stronger than ever provides a powerful tale of hope for cities and people rebuilding their lives in the wake of nature’s fury.

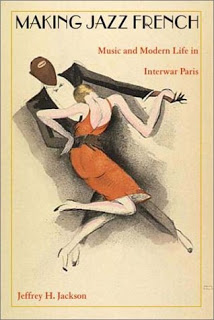

In my first book, called Making Jazz French: Music and Modern Life in Interwar Paris (Duke University Press, 2003), I studied the reception of jazz music in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. I wanted to understand what Parisian listeners thought about jazz when they heard it and what it meant to them at a critical moment in their history, just after World War I. I found that the reactions of audiences were quite mixed. Some people praised the music as the sound of the modern age, but others feared that it would cause their culture to disintegrate. Many people understood it as either the beginning of "Americanization" and the arrival of the machine society, or as “black music” that would cause France to revert to a primitive and savage society. In the end, however, audiences, music critics, and French musicians themselves changed the way in which Parisians thought about this music. They turned it from something strange, foreign, and exotic into a sound that was pleasing and exciting: they “made jazz French.”

I have also co-edited three books. With my history department colleague Robert Saxe, I published The Underground Reader: Sources in the Trans-Atlantic Counterculture. Every society has rebels, outlaws, troublemakers, and deviants. This collection of primary sources takes readers on a journey through the intellectual and cultural history of the “underground” in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It demonstrates how thinkers in the US and Europe have engaged in an ongoing trans-Atlantic dialogue, inspiring one another to challenge the norms of Western society. Through ideas, artistic expression, and cultural practices, these thinkers radically defied the societies of which they were part. The readings chart the historical evolution of challenges to mainstream values -- some of which have themselves become mainstream -- from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the present.

A collection of essays about cafés in European culture titled The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy, and Vienna (Ashgate Press, 2013) I co-edited collects research from an international group of scholars about the role that cafés have played in shaping intellectual debate, creative endeavors, and the urban settings of which they are a part. Authors look at cafés as sites of intellectual discourse from across Europe during the long modern period. Drawing on literary theory, history, cultural studies and urban studies, the contributors explore the ways in which cafes have functioned and evolved at crucial moments. Choosing these sites allows readers to understand both the local particularities of each café while also seeing the larger cultural connections between these places. For a short essay that explains the relevance of the café to today’s culture, see an essay I co-authored titled “Work Should Be More Like a Café.” { http://www.wondersandmarvels.com/2015/03/work-should-be-more-like-a-cafe-2.html}

A musicologist friend and I co-edited a collection of essays called Music and History: Bridging the Disciplines (University Press of Mississippi, 2005). This book brings together the work of junior and senior scholars in the fields of musicologyand history to reflect on the ways in which practitioners of these two disciplines can collaborate and learn from one another.

Life Experiences

I have lived in the north and the south: from Nashville to Boston to Rochester, NY, and now to Memphis. My travels have taken me across the US and Canada and to England, Italy, Spain, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Japan, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and of course to France many times. I began learning French in the first grade, so it seems only natural that I would come to study a place with which I have such a long history with the language and culture. For fun, I enjoy travel, reading and watching trashy TV.

Education

B.S., Vanderbilt University, 1993